When JFK declared that the American destiny of the 1960s was to reach the Moon, more than a political statement had been made. A restructuring of the paradigm in which the country had existed for half a century was able to occur through the sheer visual and intellectual audacity of a singular undertaking. Mankind was offered a new way, one that sought to distance itself from the unsettling age of physical combat that had crushed its physicality, in order reinstate a dormant hope that the only worry of the future lay in the capacity to dream of it. With its new mission in hand, the nation cultivated some of its most talented mathematical and engineering minds in an unknown field of study. It’s strange to think that this moment—in which a revolution of technology unfurled—would compete for headlines with Jimi Hendrix, political activism, and global atomic brinksmanship.

It’s said that when one is afforded generous swaths of time with no goal in sight that often nothing of profit arises. The true legacy of the words in JFK’s statement lay in his implication that all of humanity was effectively being born anew, bounded by nothing, literally breaking with terrestrial shackles. It was a second Declaration of Independence, drafting out a future at a time when it never seemed more impossible to escape the present.

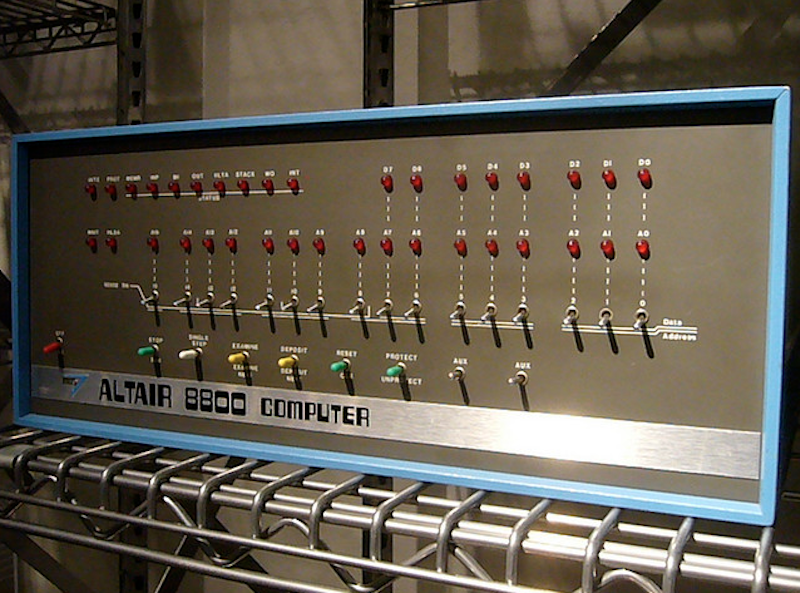

So we went to the Moon, and we came back to Earth. In the after-party the newly sharpened minds of a generation would prove restless. Computers had moved out of the realm of science fiction film props and into the homes of the average citizen, where they served as learning aids to students and young families. A second revolution was quickly beginning to take shape around it, though this time its trajectory was not entirely clear even to those within the industry.

The details of an intricate network protocol designed for the sole purpose of serving academic research does not in hindsight smack of mass appeal. To arrive at the possibility that a new Library of Alexandria could be created from its principles by the time of the mid-90s is an idea that seemed as attainable as the Moon did in the 50s. To make the odds more confounding, developments in technology had by the time of the Internet’s birth proved to be less predictable than in the past. Perhaps it is telling that somewhere in this abstract realm of computer programming and infrastructure lay a second revolution that only the children of the space exploration generation before them could have seen, much less cultivated.

Given that our detailed social and personal history now chronicled by the minutiae of search engines and social media, it is a moot point to state that the rise of the Internet has had with it mixed results. The new pilgrims of Alexandria are arriving at a destination with arguably less definitive curators than came before them. More confusing is the logical conclusion of this new democratic process that though scientific hands have spun this web of information it must be made accessible to all. In the search for new knowledge now come the accompanying perils of pickpockets, charlatans, and cultists.

The very vision that this elicits, never more remote from the thought of zero gravity, begs one to ask the compelling question of why the second revolution of our century, information, does not strike with the same singularity that moved Americans beyond our atmosphere and into space. Perhaps it is just too difficult to answer the question of what the Moon looks like when the clouds aren’t right.

The Great Information Revolution

Post-space race, a new revolution began.