By now everyone has heard the polyphonic din of old and new media trying to figure out what to do with the Internet. Critics both hoary and fresh-faced have told us what to think of social networking, Twitter, and the democratically ubiquitous blog. I have followed these arguments inattentively at best since they seem about as vital and exciting as two Shar Peis fighting in a pillowcase, but I have noticed that the focus seems to fall mostly on new media forms’ political and public importance. Blogs, tweets, and MySpace pages often get diagnosed as a source of information, a digital transformation of the town crier rather than, for instance, the novel, the poem, or the play.

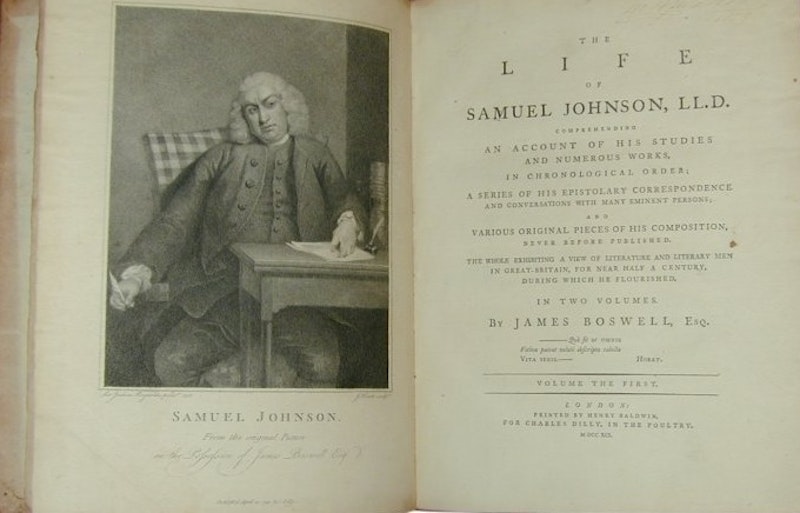

I’ve recently begun reading James Boswell’s Life of Johnson, a work in which I possess shallow expertise if even that. The Life debuted in 1791 and is held to be one of the finest (and certainly one of the longest) biographies in the English language. It’s a delight because Boswell, a superlative writer himself, doesn’t clumsily attempt to fit Johnson’s life into a master-narrative of the times, nor does he lose himself in minutiae. Boswell gives detail only where the narrative requires it, and he supplements the plentiful written records of Johnson’s life with interviews and correspondence with his contemporaries. The work is such a peerless picture of Johnson that the actual substance of the great writer’s life recedes into the background—knowing what Johnson did is secondary to the joy of watching Boswell resurrect his old friend.

I recall a biography of Gandhi that I attempted to read in high school, a work which bored me into a stupor by sedulously eradicating every trace of personality from its subject and by clothing him in political portentousness. Gandhi was a man who held famously unusual habits, yet this bad biography reduced him to an automaton who said and did what a predetermined macro-historical narrative required of him.

Boswell places no such fetters on Johnson, and perhaps this is why people are still reading his masterpiece over 200 years later. Praising Boswell for being a good biographer is, to invert Johnson’s own phrase, “blacking the chimney,” but as I read his unhurried account of Johnson’s intense, literary, snarky life I thought to myself, I’ll be damned if this isn’t a little bit like Facebook. Like Facebook, the Life of Johnson gathers in one place many of the threads of a gregarious life. Boswell accumulates Johnson’s writings and those of his contemporaries, and in many cases their opinions on one another. He collects testimonials on Johnson from his family and acquaintances. He reports, whenever possible, Johnson’s famously witty epithets. If he had been able to collect photographs his great work would have resembled Facebook even more forcibly.

With Facebook the pieces accumulate as people create them—friends leave wall messages (often cryptic), people post news stories, or in my case links to their own moderately interesting articles on toiletries, and throughout people leave comments, usually no more than a few lines, expressing approval or disgust or skepticism. Of course Boswell’s account is a literary masterpiece because Boswell has sorted through the wrack of Johnson’s life and picked out the important and interesting things, and furthermore he has arranged them in a comprehensible format. Facebook doesn’t do us that favor; it’s more like the sources from which Boswell worked.

But take, for example, an early controversy about Johnson’s regard for the poet Milton. Boswell recounts the story of William Lauder, “a Scotch schoolmaster” and closet nutcase who elaborately and at great length fabricated Latin sources that made Milton look like a plagiarist. This scholarship impressed Johnson, who wrote a preface to Lauder’s expose; this led some of Johnson’s other biographers to conclude that Johnson despised Milton. Boswell gathers enough glowing praise of Milton from Johnson to dispel that misconception completely. Boswell’s account is rather more prettily written than mine and goes into greater detail, but the basic fact is that this was a social tiff over literature and that it could have (barring technological hurdles) taken place over the Internet; it did take place mostly through letters and publications.

There are quite a few very funny glosses of classical literature floating around the Internet in the form of long lists of Facebook statuses. If you’ll forgive me for explaining an obvious joke, these are funny because they wed the unadorned casualness and everyday dullness of Facebook with the ludicrous plots and epic action of great classics. This wouldn’t really work for the Life of Johnson because the distance between the genres is, perhaps surprisingly, too short. Facebook hasn’t been around too long, but can we imagine an entire life recorded in status messages, wall posts, and annotated photo albums? What a strange transformation for biography, a genre distinguished by careful interpretation, exhaustive research, and a focus on the famous. It may be silly to ask if Facebook is every man’s brainless, cybernetic Boswell—perhaps a better question is, what, if anything, does this mean for literature and for people?

Facebook and The Life of Johnson

Were Boswell alive today, he might be trolling social networking sites for biographical research.