(Update below)

If there were a list of the 10 most important books written about the Internet’s social and political impact over the last decade, Larry Lessig and Cass Sunstein would be responsible for half. The two law professors and friends have been visionary in extending the logical implications of radically diffuse communications technologies into traditional social structures, although from two slightly different perspectives. Lessig’s work is closely aligned with Silicon Valley, focusing on deep technical specifics of the Internet and the processes of cultural production. Sunstein (also an editor at The New Republic) is oriented towards the Washington policy world with work that speaks more to accountability, communication, and knowledge-making in a democracy.

When these two thinkers pool their collective intellectual heft and name-recognition together for a common cause we should assume that they’re onto something significant. When they also enlist noted feminist philosopher Martha Nussbaum as an ethical center of gravity, we can be sure of it. Such a joint-force operation recently occurred at a University of Chicago-sponsored conference on speech, privacy, and the Internet.* Working against the liberationist theology espoused by many technophiles, the conference sought to ground specific problems created by the Internet in much older problems of ethics and law. The conclusions reached suggest that, like so many frontiers in human history, the Internet too will be civilized.

As a communications technology the Internet unquestionably distributes the tools of speech to more individuals than ever before. It also—unquestionably—has led to more anonymous speech than ever before. These are two fairly straightforward observations, but they are often taken to mean more than what they actually are. Like so many technological revolutions and fads, empirical facts about the Internet are too quickly assumed to reveal something normatively inherent about the Internet (if it has any inherent character at all) that portends some significant change in human nature. It is, after all, far easier to argue for revolution than to engage in the challenging and complicated work of re-stating our eternal questions in the latest jargon.

While acknowledging the many obvious benefits of the Internet, the participants at this conference held that the wide distribution of anonymous speech had significant harms that cannot justify the continued libertarian utopia of free identity now known on the Internet. The example of AutoEmit, a discussion forum for law students, came up frequently. A few years ago anonymous posters repeatedly and viciously attacked two female students in this public space. It was vile, with threats of rape, sodomy, and violence during pregnancy. Clearly, to the extent that restricting expression through threats and intimidation is a crime—and both civil rights law and sexual harassment law provide numerous precedents for this claim—a case can be made that these anonymous posters broke the law. Gangs of hackers that assault and shut down female-written blogs are another example.

According to Nussbaum, these kinds of anonymous attacks also do something even more significant. Objectification, simply defined, is the stripping down of a complicated human identity to a few salient characteristics. These two law students’ public identities were reduced to the worst slander a few deranged minds could imagine. They literally existed in no other way than as sluts and harpies to an overwhelming number of their peers, and they had almost no recourse to recover lost reputations. Putting aside whether such anonymous speech should be illegal, it seems clear that it is deeply unethical.

These conclusions are obvious, but what follows is the whole crux of the argument of the conference. In any other context slanderous objectification, threats of rape, and the like, have an established system of law for the victims to appeal to. Such a body of law does not currently exist on the Internet. Other law is occasionally awkwardly applied, but in the case of these two law students the technology of the Internet prevented the very first step in prosecuting the law: identifying the offender. The students brought a suit against their provocateurs, but AutoEmit did not keep the IP addresses associated with the offending comments.

Identity is the first step towards responsibility. Without a consistent system of identity on the Internet, crimes like this will go unpunished. Identity, however, can be construed in different ways. The conclusion of these lawyers is that anonymity is inherently unsustainable. As more and more people integrate the Internet into their social lives, the more harmful the speech crimes will be, particularly as we look forward to a future generation coming of age with artifacts from their entire lives preserved in digital form. (As Facebook and cameraphone users grow into positions of responsibility, it might be good to know who is publishing the compromising photo from college so that you can ask them to stop.) A regime of pseudonymity offers a possible compromise.

The most successful websites operate under a pseudonymous regime. Wikipedia, Ebay, Amazon.com, the Huffington Post: all insist upon a user’s identity being held, in some way, responsible and accountable to the real world. While Wikipedia, for example, can’t necessarily trace their editors to a specific real-world person, they do insist on a stable identity if one wants to rise to a position of responsibility. This pseudonym is crucial for building reputation and trust over time.

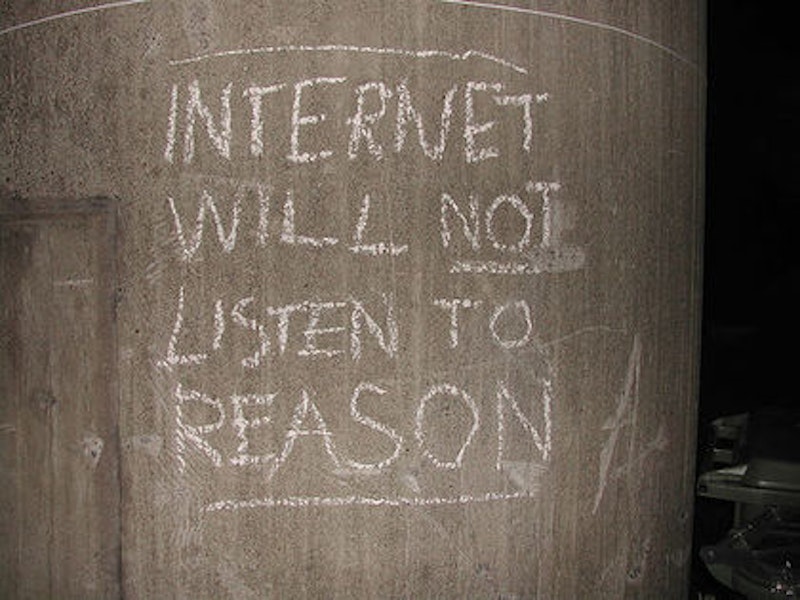

Returning to the two observations about the Internet—its diffusion and anonymity—the Internet facilitated the unethical and potentially criminal activity by the AutoEmit posters. Of course there are other social contexts where one can anonymously threaten rape—the bathroom wall was brought to mind. But there is a body of law that applies to bathroom wall speech. If caught, the writer can be prosecuted for vandalism and held responsible for defamation. The owner of the wall can be held responsible for taking down the offending comment. But putting all that aside, the most obvious difference is the scale in audience. Comparatively few people will ever read a scribble in a stall, yet there is a body of law that applies to speech acts in that medium. On the Internet, one can potentially reach millions with one’s speech, and yet there is no consistent body of law to protect victims. Think about Juicy Campus for an example.

The Internet, the conference participants argued, changes nothing substantive about anonymous speech. It merely changes the degree to which anonymous speech is possible, and questions of degree are precisely the questions where lawyers excel. A few possible solutions were thrown out, including a consistent and portable online identity similar to a driver’s license (Identity 2.0 explains this technological solution). Another idea is to have all web site owners opt in to a tiered liability structure, to hold sites responsible for what they publish and allow users a verified way to gauge the reliability of a site’s information.

The most important conclusion of the conference is that some kind of process is needed for linking speech and responsibility on the Internet. This need not be a direct real-world identity, as most can obviously see how that would take away many of the benefits the Internet provides. Properly construed, we actually see very little anonymous speech in the world except on the Internet, because anonymous speech is typically linked with a responsible intermediary like a bathroom wall’s owner, or a book publisher, or a journalist. By taking on responsibility in the case of libel, defamation, and slander, these mediators allow for a kind of pseudonymity by the speakers themselves.

Any attentive observer will worry that the imposition of an identity regime on the Internet will inhibit speech. But we might ask whether it’s really such a burden to have responsible mediators. Sites like this one take responsibility for the comments on it, as do the most successful and useful websites. Anonymity has an obvious value, but there is no reason to think that anonymous political speech must necessarily be held to an unsavory alliance with juvenile hate speech. Pseudonymity might offer a productive compromise.

Ever since its rise to popular consciousness during the 1990s the Internet has often been referred to metaphorically as a kind of Wild West. The predominant interpretation of the metaphor to date has focused on its positive and aspirational aspects. But respectable people are staking their own claim to the Internet, and just as churches and schools worked their way across the North American west 150 years ago, it appears that laws and institutions are coming to civilize the web.

*[UPDATE: Our original subhead stated that only three scholars, implicatly Nussbaum, Sunstein, and Lessig, participated in the conference. In fact there were more; a complete list of participants can be found at the symposium's website.]