Caron Pour un Homme, Yatagan, and Le 3ieme Homme

These three Caron masterpieces span almost a century of perfume history, which is like regular history but with almost no political or social significance. Each one is a creature of its time. They’re also all very good, which is a boon for cologne enthusiasts who do not wish to use a Foucauldian technique when explaining their fragrances to friends, loved ones or state authorities.

Pour un Homme comes from the 1930s, a genteel, subtle era in men’s fragrances. It blends lavender and the driest conceivable vanilla; amusingly enough these two beautiful scents combine to evoke Play-Doh. The lavender is not the biting, plasticky lavender of the Homegoods soap section—it’s planty and slightly sweet, and would probably raise the nostalgic ghost of a field of actual lavender in the Loire valley, assuming that such fields exist and that people know what they smell like. Pour un Homme does gender ambiguity in the cleanly sexless Bertie Wooster tradition, suggesting polite confusion or a refinement of manners so exquisite that it precludes the possession of sexual organs. Dandy, not David Bowie.

3ieme Homme comes from 1985, the great age of the masculine fougère—in fact, it debuted three years after the most infamous fougère of all, Drakkar Noir (they smell nothing alike). Fougère, which means “fern-like,” refers to a genre of men’s fragrances that contain lavender, oakmoss and coumarin (whatever that is). I enter a deep, renewing sleep whenever I attempt to read anything else about the secret inner life of fougères so let’s leave it at that.

3ieme Homme opens with citrus, lavender, and jasmine, then settles into a spicy powder (in this it resembles Chanel’s ubiquitous and also excellent Pour Monsieur Concentrée). This is salty and unbelievably French, like one of those old Parisian women who probably blew up trains for the Resistance and who pronounces her every word as if she is personally spitting it into the face of an SS captain.

Yatagan, from 1976, stands out from these two muted, elegant fragrances, since Yatagan relies on an almost repellent booze and civet opening and then settles (if settles is the word, which it isn’t) into a roiling, spicy, leathery base that evokes a seldom-cleaned yurt filled with violent degenerates. The 70s favored strong, rather bitter men’s fragrances and Yatagan fits with the Quroums and Halstons of its era. But there’s something endearingly excessive about Yatagan that its leathery cohorts lack. The typical 70s scent suggested that the wearer might be a barbarian in a cute, metaphorical sense; Yatagan asserts that he is actually Attila the Hun.

Civets, by the way, are an unfortunate breed of animal related to cats. They produce a repulsive musk that perfumers introduce into unexpected places for reasons known only to perfumers. And “yatagan” refers to a particular kind of scimitar. There is no reason to believe that processing civet musk requires use of a yatagan but I’m going to imply that it does.

Yves Saint Laurent Kouros

In a New Jersey Sephora in 2002 I smelled a cologne that I loved—it evoked a humid flower shop, the smell of blooms and stems and pollen-laden moisture, the sweetness of plants rather than sugar or fruit. It was beautiful, but for some reason I didn’t buy it.

I remembered that it was either Kouros or Body Kouros, two distantly related Yves Saint Laurent scents that come in charmingly rectangular bottles. The next day I went back and tried both. Kouros was foul; Body Kouros smelled okay, but not like flowers. I bought the Body Kouros and convinced myself that it was the one that had impressed me.

Nine years later I tried regular Kouros again. Kouros opens with an unbelievably foul reek that makes me wonder why anyone has ever bought it. Kouros’ topnotes, for me, evoke a memorably vile bathroom at the Bordeaux train station, a tiled cube in which human beings (and possibly other mammals) indulged their most repugnant excretory fantasies. It was so repulsive that I paid the 50 centime fee, opened the door, then immediately turned away, as if I had encountered a shattering sacred power. No American could set foot in there and hope to live.

This was a European fetor, a stench with many thousands of years of history behind it, and this history included whole generations of uncouth men (perhaps soccer hooligans) voiding their every orifice in Bacchic ecstasy. Supposedly this excremental accord (which, to be fair, suggests a filthy bathroom without precisely replicating any of its odors) comes from civet, which plays a starring role in Kouros. Civet, like the Klopman diamond, is a blessing and a curse—it gives body, interest and oily power to a scent, but if the perfumer lets it escape control it turns bad fast, and it’s not instantly pleasing to most people.

Kouros did not instantly please me in 2011, when I sampled it in a rather grim Ulta in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. I sprayed it on my wrist, thought “well that’s unbelievably terrible,” and continued walking around the store. After a few minutes I caught a hint of something luscious—I sniffed my wrist again and there was the flower shop from 2002, the beautifully complex, damp floral note that I had missed for almost a decade. I realize now that it’s actually an incense and honey accord that evokes flowers, but whatever. It’s sweet and beautiful, but it’s a dark, sardonic sweetness, and it’s very strong.

I sampled Kouros alongside Aramis Tuscany, itself a scent with balls. Tuscany came away looking like a shy, bespectacled grad student. I also tried Chanel Pour Monsieur on the same day—it was like meeting with two skinny guys from NYU and then Dracula, in the Gary Oldman bat-wolf sense. I have no idea why any normal American man would buy Kouros given its hilariously vile opening, but if you can sit that out it’s quite rewarding.

If you’re not feeling up to a doo-doo accord you can seek out one of Kouros’ “flankers,” lighter Kouros-alike scents that Yves Saint Laurent often releases in the summer. YSL included a pair of temporary tattoos with one of their more recent Kouros flankers, unimaginatively called the Tattoo Edition. I suppose this might be a selling point with some extremely specific demographic.

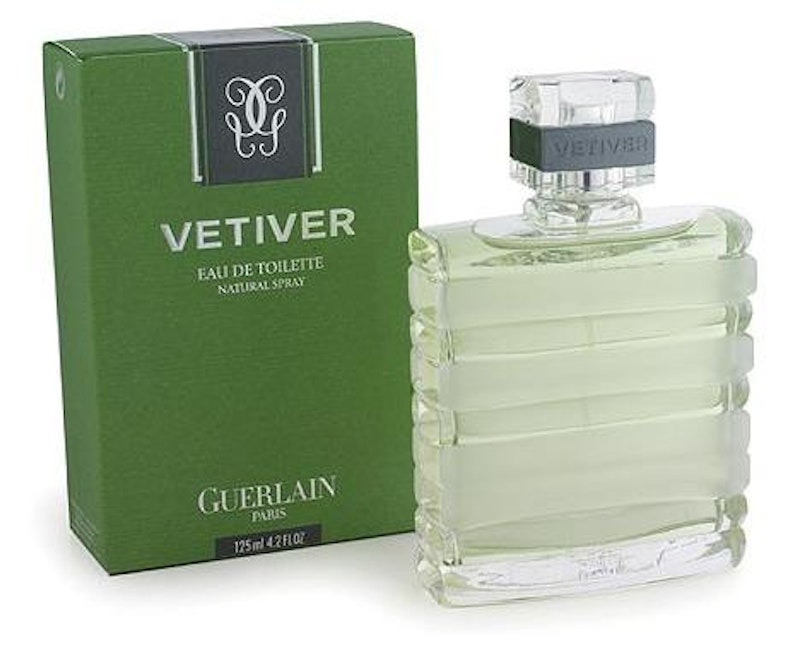

Guerlain Vetiver

Like Jean-Paul Belmondo smoking cigarettes in a marsh, at night. This is a dank, gloomy, dramatic vetiver scent with a weirdly crisp edge (crisp the way a vegetable is crisp) that keeps it smelling bracing and sharp. Tobacco and leather float in and out, but an oily, natural vetiver note dominates.

Vetiver is a grass native to India, and it’s very frustrating to write about it because it smells like itself and unlike anything else. Guerlain’s vetiver has the depth and interest that perfume connoisseurs value, but it also has a clean, wearable transparency that will appeal to people who don’t keep journals in which they refer to “drowning forever in the exquisite ecstasy of indolic jasmine.” Like Belmondo (or at least like his character in Breathless) it’s neither pretty nor nice, but it is engaging and, in its own oily herbal way, delicious.

Luca Turin, an eminent scholar of the biochemistry of smell and a surprisingly excellent perfume reviewer and writer, calls this fragrance a “reference vetiver.” So if you find yourself needing to reference a definitive vetiver scent in your daily life, well there you go.

Vetiver scents, by the way, are not exactly rare. Royall makes a bitingly medicinal, sweetly barbershoppy vetiver that lacks the Gallic subtlety of Guerlain’s. The Italian designer Etro’s luxurious, expensive pure vetiver scent smells as wild and raw as expensive Italian cologne can smell. Lalique’s Encre Noire (which comes in a beautiful black glass cube meant to evoke an inkwell) moves M. Belmondo deeper into the bog with one of the wettest, earthiest scents I’ve ever smelled. I like it but I don’t know why. Cyril W. Salter makes the weirdest vetiver of all, a French vetiver-scented shaving cream that smells like a fast-food hamburger in a Styrofoam container. If only they made a cologne version!

Chanel Pour Monsieur Concentrée

If Kouros sounds like way too much of a challenge you might enjoy this readily available Chanel offering. Pour Monsieur is both accessible (meaning nice-smelling) and well-constructed. Pour Monsieur opens with a wet, fresh citrus and then settles into spicy vanilla-tinged powder—it smells kind of like a wild, exuberant makeup bag. This falls on the butch side of metrosexual but just barely. It’s not in any way threatening, or even arrogant and egomaniacal like the classic power scents of the 70s and 80s.

I can’t imagine anyone disliking this scent, nor can I imagine any occasion for which it would be inappropriate. Luca Turin notes in his book Perfumes that Chanel and Guerlain are the only remaining perfume houses that make their own fragrance oils—this ensures a very high quality, and is also something that you can tell people at cocktail parties, assuming that you don’t care whether they hate you.

Chanel sells only the concentrated version of this cologne in the United States (perhaps because Americans are so fat?). Supposedly the non-concentrated version found in Europe is much better. Curse their French wiles!

Azzaro Pour Homme

I realized recently that I’ve seen Azzaro practically everywhere for years and have therefore assumed that it’s cheap and gross. Well, it isn’t. Azzaro Pour Homme (not to be confused with the even more ubiquitous Azzaro Chrome or the insipid Chrome Legend) is an aromatic fougère, which is different from a regular fougère in a way that’s so important and interesting that I will leave it to the reader to look it up.

Pour Homme is interesting because it smells overpowering and sour if you spray it on your wrist and sniff it; if you actually wear it you will find that it smells like the spicy cleanness of a big white bar of triple-milled soap mixed with fresh French herbs. Azzaro followed and improved on Paco Rabanne pour Homme, which has the same clean soapiness without Azzaro’s herbal complexity. Paco Rabanne is also rather good; it falls just about halfway between Azzaro and Drakkar Noir.

Azzaro releases a truly heroic number of flankers for its signature scent. You can find Azzaro re-imagined as Onyx (in a snappy black bottle) or Elixir (which adds sweet fruit), as an “urban spray” (no one knows what this means), repackaged in a leather sleeve or as a “bois precieux edition,” which comes with a cute little ebony cap. I liked this enough to order a 200-milliliter flacon to keep in a dark closet as insurance in case Azzaro decides to reformulate. This in turn caused me to put on the soundtrack for Elevator to the Gallows and stare at myself in the mirror while thinking, “so this is your life now, Samsky.”

Dior Fahrenheit

I remember going to Macy’s in 1988 with my mom; the makeup counter lady gave her a sample vial of Fahrenheit, which we opened and sniffed at home. We laughed about it—we didn’t “get” Fahrenheit, in that we thought it smelled like burning plastic and hairspray.

Well it kind of does smell like that, but it’s not a joke. Fahrenheit is another weird masterpiece like Kouros, and is supposedly a best seller for Dior, though again I can’t imagine why. Perhaps women are buying Kouros and Fahrenheit for their boyfriends and husbands, who spray the perfume once and then place it in a rarely used drawer. Fahrenheit opens with a planty-floral accord of such density that it suggests gasoline; it’s like one of those collages of scenes from Star Wars that forms a picture of Yoda.

As a technical feat the gasoline opening is quite impressive, though it seems a trifle weird for a mainstream cologne. After a few minutes Fahrenheit dries down into a less imaginative (though still excellent) flowers-and-leather scent, a pleasant masculine fragrance disfigured by an arched eyebrow and pursed lips that suggest that it’s just about to do something unpleasant.

Fahrenheit too boasts flankers, like Fahrenheit 32 (Fahrenheit for 10 seconds, then the creamy synthetic vanilla of soft-serve ice cream), and Fahrenheit Absolute, which contains oud, a middle eastern wood essence that has grabbed the attention and money of the perfume obsessive community. This summer Dior will release Fahrenheit Aqua, which will presumably include calone, the molecule that gives the 2,000,000 aquatic scents on the market now their salty seaside freshness.

Guerlain Eau de Cologne Impériale and Eau du Coq

Impériale debuted in 1853 and du Coq in 1894: both are still sublime. In perfume-talk eau de cologne refers to a scent with a low concentration of fragrance oils but also, and more importantly, to a fresh, citrus-herbal style of fragrance. 4711, which you can sometimes find in a huge jug at the drugstore, claims to be the first of this very old genre.

These two similar Guerlain colognes open with a very wet, refreshing bergamot and citrus. They stick around for an hour, which they spend sparkling and smelling wonderful, and then politely disappear. Eau du Coq (whose name will surely provide many an enjoyable titter) contains a courtly, subtle shadow of civet, which lends it a bit of a smirk. Impériale does the cologne thing without du Coq’s irony. These two are most certainly unisex—no one gender has claimed citrus. YET.