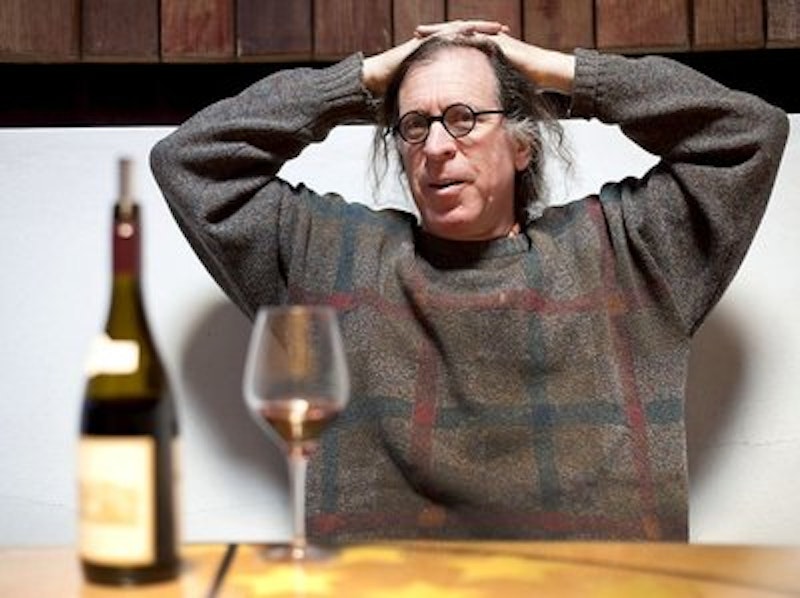

Winemaker Randall Grahm is a wine rebel—self-proclaimed "terroirist." That is, he's obsessed with making what the French call vin de terroir—wine that reflects a sense of place. He calls it "the only wine that matters." The soil, climate and terrain in any particular location where grapes are grown form a unique combination that he insists must be reflected in the wine produced in that location. This puts Grahm (with whom I corresponded by email for this article) at odds with many of his fellow California vintners—the ones amping up their wines so that they're described as "flamboyant," "intense," and "big." Subtlety, minerality and nuance, however, are what this Santa Cruz-based "terroirist" seeks.

A California wine pioneer with over three decades of experience in the business, Grahm's career has been far from orthodox—he described it as "byzantine, labyrinthine"—but what else would you expect from the guy who popularized the use of the screw cap? After majoring in philosophy at the University of California Santa Cruz, he got his introduction to the wine world while working at The Wine Merchant, a Beverly Hills wine shop, where the opportunity to taste such magnificent wines as the '49 Comte de Vogüé Musigny and the '64 Cheval Blanc propelled him to complete a degree in plant sciences at University of California Davis' internationally-acclaimed Department of Viticulture and Enology.

Early on in his career, Grahm was obsessed with producing pinot noir. The pinot noir grape is notoriously difficult to grow, which is what attracted him to it. It was a "guy thing," as he put it. A chance to test his mettle with the trickiest grape. He tried growing the "perfect" pinot noir grape at his Bonny Doon vineyard, but it didn't live up to his lofty expectations, a winemaker's pitfall he refers to as "The curse of the home-ranch fruit." After experimenting with making pinot noir from grapes imported from Oregon, he soon decided on another path to salvage his career as a wine-maker—Rhône varietals—which eventually led to his appearance on the cover of Wine Spectator magazine in 1989, posing with a horse, a cowboy hat, and mask as the "Rhône Ranger."

By the time Bonny Doon had been in business for 23 years, in 2006, the winery had become the 28th largest in the U.S., shipping 450,000 cases per year. Facing apparent "success," Grahm then took the road less traveled. Deciding he didn't want to compete with "real" wine companies, he downsized, selling off two big labels. Success had left him feeling he’d left his original values and idealism behind, that his wines were not "necessary." He wanted to make great, unique wines that would "make the world more interesting."

With this unanticipated turnabout, Grahm's passion for terroir became the driving force in his professional life. Previously, in his quest for more "flamboyant" wines, he used what he calls "designer yeasts" and enzymes to amplify the end-result. He began to find that indigenous yeasts and no enzymes make for more interesting and subtle wines that are less "exhausting," like that witty person at a party who talks a little too much, to use one of Grahm's analogies.

Now Grahm’s embarked on another wine adventure. He’s set out to create a unique wine—a new vinous expression he calls a "Grahm Cru"—at his Popelouchum Estate in California's San Juan Bautista. The plan, a non-profit, is to create a heterodox vineyard by cross-breeding Vitis vinifira plants to produce 10,000 new varieties of grapes that have never existed before, and then blending them into an original cuvee—the Grand Cru of the New World—which he likens to the discovery of a new star or new species. The great variety of new, distinctive grapes will work to suppress the varietal character, serving to highlight the unique characteristics of the soil.

Grahm says that he sometimes thinks of himself as Woody Allen, in that some people preferred his earlier, lighter offerings to his later, more serious work. He wants to leave a legacy that others can then build once he's done. With this final paradigm shift, Grahm’s making his boldest statement yet in his journey in search of the elusive, true vin de terroir. He describes this as a "profound sort of letting go," and that's because the earth is calling the shots with the wines he wants to make, not the vintner. Grahm says it's a matter of "seeing what's really there. What the vines and the land are telling you." What he's attempting involves what he describes as a shattering of his ego in search of enlightenment, or a true spiritual path. This calls for mastering a whole new set of skills, something rare for someone with over three decades of experience in the wine business. He likens it to trying to run a marathon at 62 without ever having run a race before.

—Follow Chris Beck on Twitter: @SubBeck