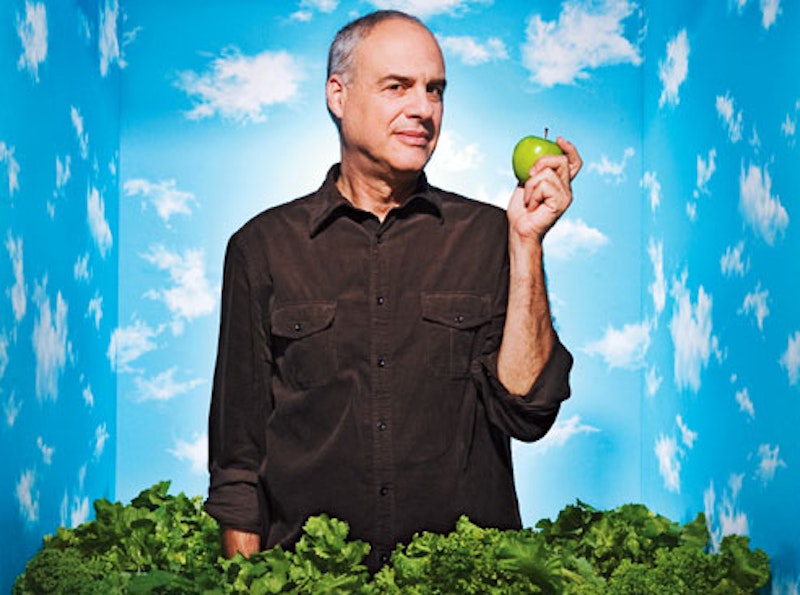

As the author of The New York Times’ food column, ”The Minimalist,” Mark Bittman has championed the virtues of no-fuss, healthy eating for over a decade, predating the more recent cultural emphases on “organic” and “green” foods. His voluminous cookbooks, How to Cook Everything and How to Cook Everything Vegetarian, have also becomes staples in many contemporary American kitchens, including my own. As Bittman’s public profile has grown—he now appears regularly on The Today Show and traveled with Gwyneth Paltrow and Mario Batali for their series Spain: On The Road Again—so has the social concern in his writing; his most recent book, Food Matters, out in hardcover earlier this year, is half cookbook and half well-researched eating guide, stressing moderate consumption habits and fresh ingredients as alternatives to the processed Big Food products Americans more commonly eat.

I interviewed Bittman by phone to ask him how he balances his work in print, blog, television, and online-video media; how he’s seen global cuisine change in his 30-year career; and who, if anyone, he considers to be his professional forebears.

SPLICE TODAY: Tell me about your career. How does a young man with no professional or educational culinary experience eventually become the author of multiple cookbooks and a food columnist for the Times?

MARK BITTMAN: Well, when I graduated college, I worked as a community organizer, which is about the only thing I have in common with our president. And in this community organization, which was in Boston, I ran the newspaper. At the time, I was most interested in photography, but I also did writing and editing and layout, as well as photography. And that was kind of like my graduate degree. Meanwhile, I was cooking as a hobby, and when the newspaper ended and it was time to try and make a real living, I started to freelance, as a restaurant reviewer in New Haven—really, I wanted to write about cooking; I wasn’t particularly interested in being a restaurant reviewer. But I did some restaurant reviews, and I wrote about wine a lot back then.

But no one wanted me to write my kind of recipes. This was in the 80s, when people wanted really more complicated things. Fortunately the pendulum swung around the early 90s or so, when I had more experience and better credentials, so that meant I could publish more and more of my own work things. Then I wrote Fish, and then I wrote How to Cook Everything and the first book with Jean-Georges [one of two collaborations with French chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten] and got the column at the Times. Those last two things were big, and happened around ’97 or ’98.

ST: Your work, to use your terms, is as much about eating as it is about cooking. Apropos your recent Times piece on seafood farming, what do you consider to be the most damaging development in American eating culture over the last 60 or so years? Certainly in the early sections of Food Matters, the bad guy looks like the USDA.

MB: I would point out that Food Matters was a work in time, and though I haven’t changed my mind about anything in there, I would say my thoughts have evolved some and maybe become a little more refined. This isn’t my way of excusing the USDA but maybe of saying that, while I don’t think the USDA has done its job, it’s been overwhelmed by marketing practices that began in the early 50s and now run to tens of billions of dollars every year.

So I guess the worst thing is our under-funded USDA, or at least its under-funded education arm. I don’t care if you think Michael Pollan is the most intelligent person in the country, [he can’t compete] against Coca-Cola and McDonald’s, who can put a billboard anywhere they want, build a store anywhere they want, or give their product away for free in the short term to make money in the long term.

We are starting to be heard, which speaks to the good developments. Starting with Pollan, who I think of as a visionary even though that term scares the hell out of me, we’ve seen people in the last five or 10 years who have taken up the cause of really good food and good eating—not just “exquisite” eating, but solid, real eating. And they’ve done that without being elitist about it, or silly about it, and though there are still those aspects to what we do, I think we’re starting to see that good food can be had everywhere and that fresh ingredients make for good eating and good health. So I’m happy about that, and I’m happy to be part of that so-called movement.

ST: So when you started the Minimalist column initially, did you perceive there to be that kind of political dimension to it? It’s generally about convincing people at home that cooking and eating well doesn’t have to be a luxury, but has that only recently, with Pollan and the “movement” you mentioned, become a political thing?

MB: It’s a complicated question. As far back as I can remember, or at least for the last 20 years, my measure of success has been, “If I can get more Americans to eat rice and beans one night a week, my career would be amazing.” That would be an astonishing, fabulous thing. So is that a political statement? I don’t know what you think, but I feel it is. Is it a political statement on the level of equating cows with atom bombs? No, it’s not. I’ve gotten progressively better recognition so I can say things more seriously, things that are a little closer to my heart.

ST: What's your relationship with Pollan? You seem to be in agreement regarding an ethos of consumption (namely, “eat less”), but he addresses more big-picture cultural developments whereas you seem aimed at the individual eater. Do you see yourself as doing the same kind of work, or do you feel more aligned to the chefs, like Batali and Jamie Oliver, that you spend time with on your cooking-focused shows?

MB: Well I think neither, really. I mean, [Pollan]’s an academic who does terrific long-form journalism, a university journalist or whatever. He writes for the Times two or three times a year at the most, and I write for it five times a week if you include the blog—almost all short pieces. I consider myself a working journalist and a cookbook author; he’s a professor and a journalist and a food book author. We have talked, we’re friendly, there’s a common goal, but there are plenty of differences.

ST: Let's talk journalism. You started at the Times in 1990, and began The Minimalist a few years later. You've been doing videos in that capacity for years now, since before the current industry freak-out made publishers (belatedly) realize the necessity of online-only content like video and audio features. How has your work changed in the past year, or five years, as media focus has shifted online?

MB: Well obviously there was no “online” when I started the column. As I said, my own recipes weren’t super welcomed 25 or so years ago, and now they are, so that’s one way things have changed. As for the industry, it’s the same for me as it is for anyone else—there’s a bigger online component now, and whether that component, or the social networking is overrated, that remains to be seen. I don’t believe print is dead. I’m not convinced all the super short-form stuff—Facebook, Twitter, and so on—is all that important. And I’m not convinced there’s not room for expertise, because sometimes it seems as though everyone believes that everyone’s input is equally valuable. Call me old-fashioned but I guess I don’t get that.

ST: But when The Minimalist started incorporating video content, was that in response to industry changes, or just because it was a natural progression for a cooking column? It certainly makes more sense to have cooking videos than, say, equivalent content from political or cultural writers.

MB: I’m sure you’re right, and that’s one of the reasons I was among the first regular journalists doing online multimedia, and I think the Times saw there was an opportunity for that kind of material online. It made a lot of sense. But [before online media became so universally essential], the Times had something called New York Times Television, so my videos are kind of a continuation of that.

ST: Since your current jobs mixes blogging, video production, appearances on The Today Show, travel (particularly when you're shooting something like the Spain show), and book- and article-length writing, what's a typical Mark Bittman workday? How much time do you spend doing research, or writing, or cooking?

MB: Oh, there’s no typical day. I couldn’t answer that question. I’ll often get up around four or five in the morning and work for three or four hours, then grab four or five hours of personal time, then go back and work until seven or eight or so. Then other days, if I have The Today Show at seven or something, I’ll go for a run beforehand. I mean, every day looks different, and that’s why things are great right now—there’s no pattern, no routine. That means there are days when I wish I could just sit and work, but there are also days when I do get to do that. I just couldn’t tell you ahead of time which days those will be. Often Sunday is a quiet day of straight work. It’s unpredictable.

ST: How about your schedule as a home cook? How many times are you cooking at home versus going out, for instance? And how often are you trying out something news for the column or a book?

MB: I would say I cook six times a week, on average, and four of those times I have no idea what I’m doing, and hoping that it works out. Other times I might be just making pasta or something, or a salad.

ST: What's your favorite city as an eater? Is there a particular region or city, that you love to go back to, or a place that helped you learn to love cooking?

MB: Sure, there were places that kindled my interest, but now, I pretty much get inspired wherever I travel. Even though I see fewer new places and discover fewer new techniques. As I’ve gotten to know more, international cuisine has become more homogenized, but I still find places that are inspiring. That remains, that still happens.

ST: In your time traveling, whether as a journalist or before that, which region or country has changed the most significantly? Have any specific foods or styles proven especially adaptable?

MB: Well, the area that’s changed the most is the United States. And as for the most adaptable, that would have to be Italy. That’s a common answer, but I think what’s most interesting about it is how it’s taken the place of France. It’s ironic, or maybe indicative of trends: Italian food was underrated (Julia Child admitted she didn’t get why anyone cared about it) and now it’s overrated; French food was overrated and now it’s underrated.

ST: When you say the U.S. has changed the most, what do you mean?

MB: I mean that, when I was growing up, it was almost impossible to get a good meal in this country and now there isn’t anywhere that you can’t. That’s enormous.

ST: With all the different facets of your current job, do you feel like you have any career models? Is there anyone you think of as the progenitor of this kind of work?

MB: There were models when I was younger, but I think at this point, with the online stuff and the video and the multimedia, I think it’s gone beyond that. My models—who may have done television or journalism or cookbooks but certainly not all three—were older people, long since dead. I should note that there’s a happy exception there in Jacques Pepin, who was incredibly kind to me and thankfully is still doing wonderful work.

ST: And who were those other models?

MB: Well, Craig Claiborne was, very early, important to me. James Beard, you know, Julia, the usual. But you know I did start working in this long enough ago so that I got to meet and even eat with all of them. That was inspiring to me, and I always swore that if I became successful I’d try to be as kind to young writers as those people were to me. And I try to do that.