I used to think Kool-Aid was just a nice drink. If you open the leather-bound family photo albums in my parents’ living room, you’ll surely find a few old photographs of me as a toddler, blond and chubby-cheeked, with large brightly-colored circles around my mouth, the lower half of my face stained with artificial cherry powder. When I got a little older, I began selling glasses of Kool-Aid on the corner with my friends for 50 cents apiece, usually making about five bucks before drinking all of our inventory.

I have nothing but fond memories associated with this sugary beverage, which turns 95 this summer, but I’ve noticed that it’s received a bad rap for a while now. It started about 44 years ago in Guyana, when a cult leader named Jim Jones fed hundreds of his People’s Temple followers cyanide-poisoned Flavor-Aid—which, for the record, I’m against. Still, most forget that Jones cheaped out and used an off-brand alternative. (If you’re going to organize a mass suicide, at least buy the real deal. Could label brand Kool-Aid have prevented the terrible events at Jonestown? We’ll never know for sure.) But as is so often the case, the facts didn’t matter. Ever since Jonestown, “drinking the Kool-Aid” has become shorthand for a lack of critical faculties and a willingness to buy into bullshit.

It wasn’t always like this. Prior to Jonestown, the strongest cultural association to Kool-Aid was Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Published just over a decade before Jonestown in 1968, the book chronicles Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters’ journey across the US in a school bus full of LSD, throwing wild parties with acid-laced Kool-Aid. In this narrative, Kool-Aid was the drink of choice among those who wanted to turn on, tune in and drop out, an indirect means of unlocking the doors of perception—or, to use a more germane metaphor, bust through the walls of perception. But every Woodstock needs its Altamont, and the pure, innocent act of lacing Kool-Aid with drugs and feeding it to unsuspecting people would eventually take a dark turn in November of 1978, when Jones poisoned almost 1000 people and ruined Kool-Aid’s good name.

Today, everybody—from Trump supporters to Biden supporters, from anti-vaxxers to pro-vaxxers—is drinking the Kool-Aid, which is part of my problem with the phrase. It’s not enough to just say you disagree with someone anymore, that they’re mistaken or just plain wrong. They’re drinking the Kool-Aid, gullible saps that they are, from the fount of ignorance and disinformation that we, in our great wisdom and righteousness, have carefully avoided. As much as I disagree with Trump supporters and anti-vaxxers, and no matter how apt the comparison may seem, liberals’ general willingness to reduce them all to credulous cultists is part of why they fucking hate us so much. (It’s worth noting that this goes both ways: when Bob Woodward questioned Donald Trump about the responsibility of privileged whites to try to understand the anger and pain in the black community, Trump responded, “You really drank the Kool-Aid, didn’t you?”)

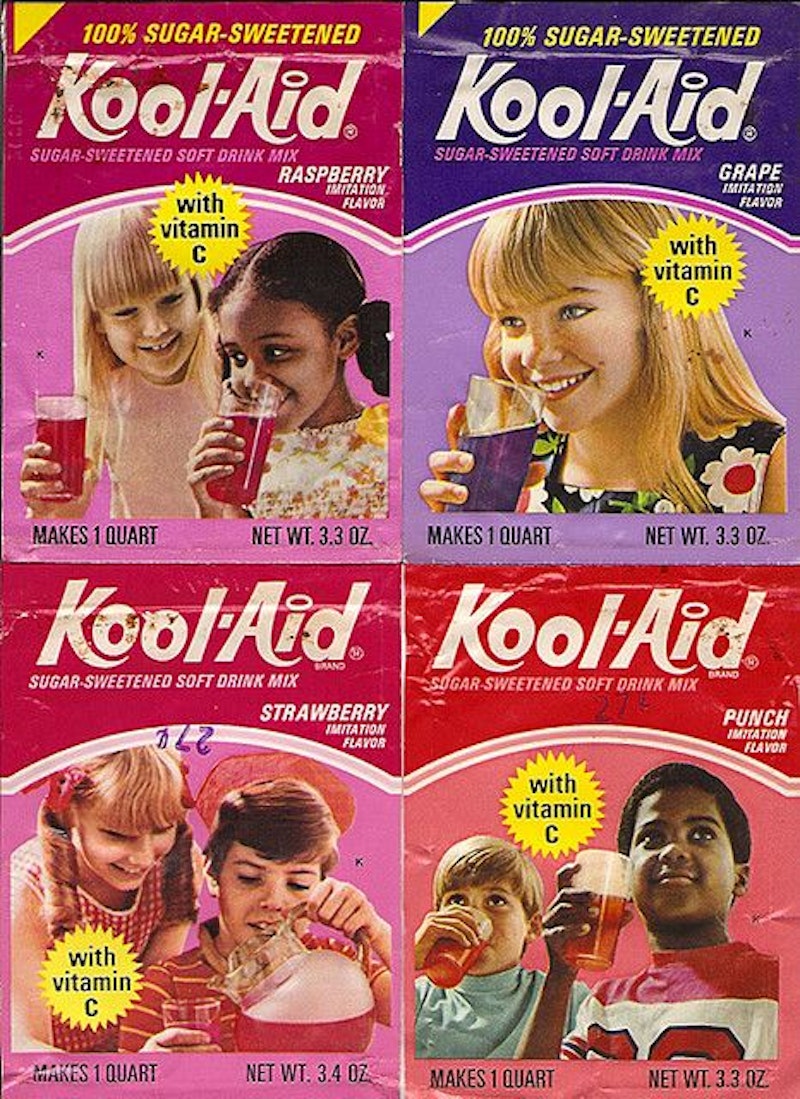

Keep in mind that Kool-Aid never asked for any of this. Before and after Jonestown, Kool-Aid has always been a flavorful drink with a hilarious mascot (a trailblazer for the plus-sized community), and the continued association with mass suicide seems downright slanderous. We need an alternative. Recent years have seen the emergence of the extremely similar red pill/blue pill analogy. While online misogynists using trans artists’ ideas to explain why women won’t fuck them leaves me feeling uneasy, it’s at least nice to see Kool-Aid catch a break.

Other alternatives to “drinking the Kool-Aid” include “buying the NFT,” “reading the horoscope” and “seeing the Marvel movie.” But if we’re looking for something that packs the same offensiveness and disrespect for tragedy, “wearing the Nikes” is most appropriate: a callback to the 1997 mass suicide of the Heaven’s Gate cult where all members were found wearing the same plain black Nikes. A shoe company with a long history of ugly labor practices—whose most devoted consumers do have a tendency toward cultishness—is a better point of reference for mindless, unyielding loyalty.

So happy 95, Kool-Aid. I hope by the time you’re 100 we’ll have learned to put some respect on your name.