One usually doesn’t associate consumerism with Communism but in Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia, where I grew up, it was alive and well (certainly during the 1980s). Leftist or pro-Communist Americans like to use Yugoslavia as an example of “socialism with the human face,” but it’s one of those trite and meaningless phrases that can only be glorified (and perhaps even conjured) by Western leftists. People still went to prison for anti-Communist sentiments and activities, although as the late-1980s approached, Communism became a meaningless ideology and regime, only to be supplanted by a different kind of ideology and the ultimate consequence: genocide against Bosnian Muslims.

As a teenager growing up in Bosnia, I couldn’t care less about politics. I was watching MTV and American movies, and desired things. Whenever something was fashionable, I wanted to have it. I was rarely able to get the original thing. I was always stuck with some off-brand item, which made me slip into a pit of mediocrity (when it comes to materialism anyway).

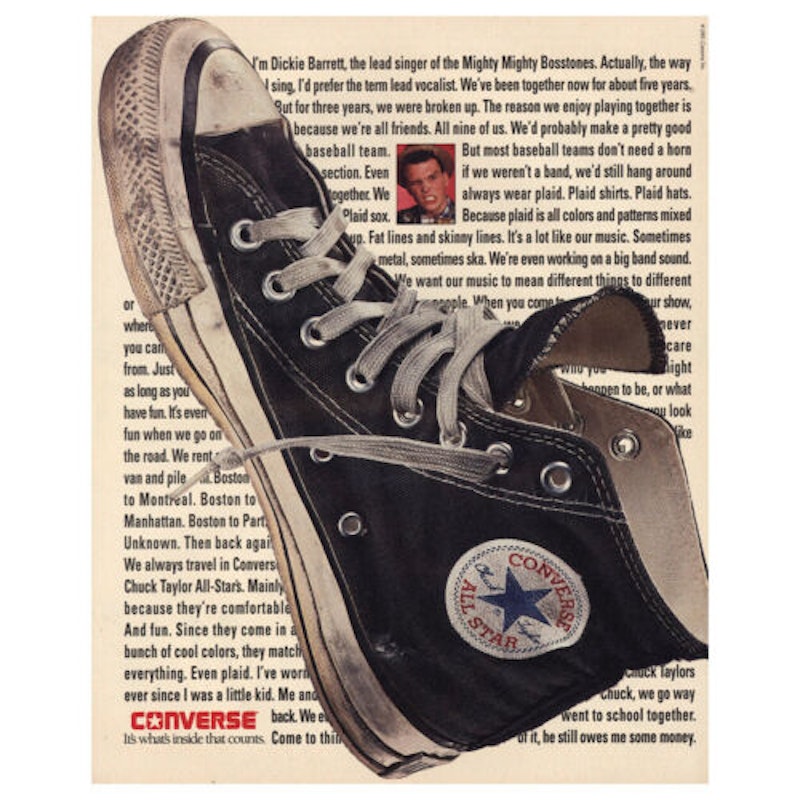

One particular item that I became fixated on were sneakers—Converse All-Star Chuck Taylor’s. I wanted them. It was like a holy grail, a jewel or an artifact that Indiana Jones is going after. My neighbor owned the pair, and I was constantly admiring them. I wasn’t really good friends with the girl who wore Chuck Taylor’s. She was nice enough, although her sister was unpleasant. They referred to their parents as “old geezers” which was unimaginable to me. They listened to the Clash, Depeche Mode, and the Sex Pistols, and always wore black. While I listened to Madonna and New Kids on the Block (I realize the shame here of openly confessing to being a NKOTB fan), they were rebellious punks, and I admit I was jealous.

I can’t recall whether my punk neighbors managed to smuggle the sneakers from the West or whether they had more money to buy them in Yugoslavia. I settled for the off-brand Chuck Taylor’s. They were black but that distinct front, white rubber was wider and somewhat misshapen. The length was ankle-high and it had a feature that Chuck Taylor’s didn’t: the sides of the sneaker snapped and you could extend them, effectively making the sneaker into a canvas boot.

My off-brand sneakers were better looking, flexible and comfortable. But they didn’t have that American, All-Star stamp, which was essential for my continued existence.

The war came and I somehow managed to make it to America. My off-brand sneakers were long gone but my desire to own an original pair of Chuck Taylor’s never went away. It took a few years of living in America before I could afford to buy new clothes, or at least new clothes that weren't sold in a dollar store. (Most of my clothes in the early years of being in America were donations.) A pair of Chuck Taylor’s became an obsession, reconstituted from my days as an America-hungry teenager.

The day finally came. I still wanted black sneakers. No other color would do. I went against the ankle-high sneaker, and settled on the low-top. This was a major event. My shoe size was 6 ½ and I tried them in the store. Something was wrong. The shoe fit alright, but I couldn’t understand why it was incredibly flat. There was no support and when I tried to walk in them, I felt as if I was carrying a piece of lead in a canvas bag that clearly can’t support it. The shoes didn’t bend well and as a result, my walk appeared ridiculous.

This can’t be it, I thought. This is the famous Converse All-Star Chuck Taylor’s sneaker? Still, trying to prove a point either to myself or my mother, I bought the shoes. When I wore them, it was like a punishment for being obsessed with these material goods in the first place. It was a reminder that my off-brand, Yugoslavian sneaker, was infinitely more comfortable. Perhaps I wanted the shoes to make me feel American. I understood later that part of my interior disposition was already American, and that I didn’t need those sneakers after all.