I confess to a sin of omission, slightly short of mortal, of being among the few, if not the only, political reporters in the Western World who has never read What It Takes, the behemoth of a book at 1047 pages by Richard Ben Cramer. I neglected it for no other reason than I’d always considered it too heavy to lift, kind of in the weight class with War and Peace, if not heftier.

And now, as is often the case, What It Takes is finally getting its posthumous due, a little more than 20 years after its publication and review as frivolous, overblown and stuffed with too much meretricious and irrelevant fluff. The tome is now regarded by political reporters and obituary writers as one of the finest books on campaign politics, an instruction manual for aspiring political reporters. My personal favorite writing on politics is Robert Caro’s The Power Broker (which outweighs Cramer’s doorstop at 1162 pages.)

Cramer now shares the library shelf with the likes of Theodore R. White, Jack Germond and Jules Witcover and all the others who’ve chronicled presidential campaigns, only his outshines theirs, according to the pile-on of belated assessments. Even Witcover praised Cramer in a recent column as “arguably the best writer of a presidential campaign chronicle ever.”

Richard Ben Cramer—Ben—as he was known, died last week at 62 of lung cancer, induced, no doubt, by the endless chain of Gauloises cigarettes that he sucked down in his early years as a key nutrient in his daily fuel of nicotine and caffeine, the twin legal addictions of many reporters of his era.

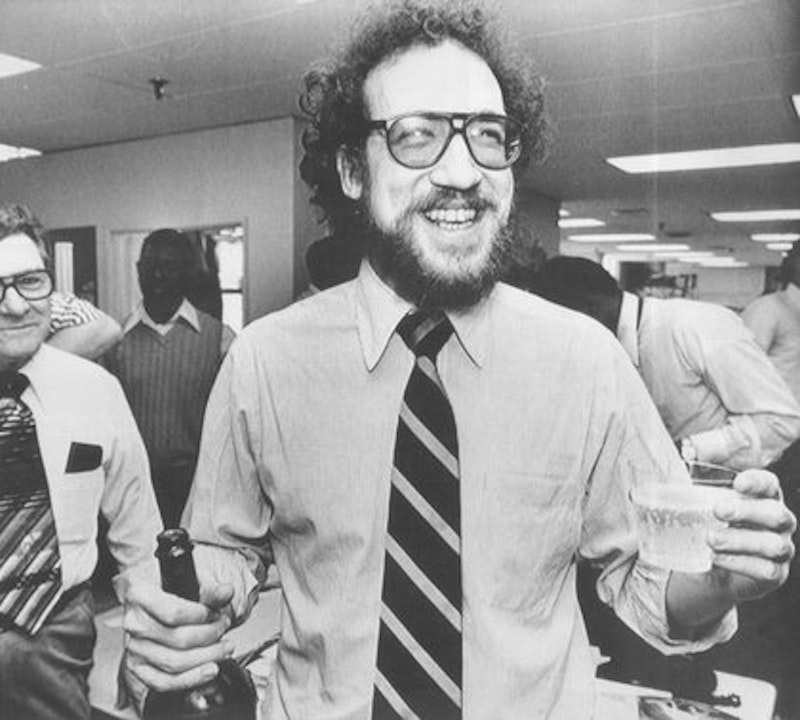

Ben was a fey spirit who prowled the Maryland State House as a reporter for The Sun in the 1970s when I was press secretary to Gov. Marvin Mandel. He was a deceptively disarming fellow, like some celestial pixie disguised in a red beard, tinted glasses and a Panama hat. The hat prompted me to nickname Ben Jean-Paul Belmondo, after the lead actor in the 60s French gangster film, Borsalino, the famed Italianate hat favored by mobsters and aristocrats the world over.

“I do remember Ben well and what a dogged reporter he was, but also how great he was schmoozing with sources,” recalls Tom Stuckey, the long-time Associated Press State House bureau chief.

It was precisely the schmoozing that made Cramer a stand-apart threat to the pack journalism of the era. He was not a bully, as some reporters tend to be, or a blowhard, as others like to pretend to inflate their importance. Ben had a style all of his own. He was an easygoing character who kind of slipped into my office and sat down on the red leather state-issue sofa and said softly, “I need reaction…” to whatever story he was working on. And before long he’d get you talking and the conversation stretched on for an hour or more. He worked his subjects in an effortless, gentlemanly kind of way and was a master at extracting information. After all, he did schmooze his way into the private lives of six presidential candidates for his masterwork.

My associate in the press office, Thom L. Burden, recalls: “My favorite memory [of Ben] is of walking into the press room and seeing Ben seated at his typewriter, eyes fixed intently on the story he was writing. Suddenly he paused, looked up and asked no one in particular: “How do you spell marsupial?” I remember feeling certain that most everyone present knew that Ben knew how to spell marsupial, that he knew that the word is an adjective and not a noun and simply wanted to share his delight at having found a way to add a colorful expression to a story on legislative business. I admired Ben’s appreciation of spice.”

There was another, softer side to Ben as well that only Baltimoreans of a certain age will recognize. Ben fell into journalism at Johns Hopkins University where he wrote for and later edited the News-Letter. While a student there, he earned spending money by babysitting the young sons of Edgar and Sally Feingold, at the time two of the city’s premier political reformers, civic and social leaders who hosted some of the best dinner parties in Baltimore.

Ben didn’t stay long in the State House or at The Sun. He moved on to the Philadelphia Inquirer where he eventually picked up a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Middle East. Shortly thereafter, we reconnected. After government service, I returned to The News American as a political columnist and Ben began a hugely successful career as a freelance writer.

Ben returned to Baltimore to write a piece on what he described as America’s Greatest Mayor, William Donald Schaefer. We had breakfast. We had lunch. Ben asked for copies of every column I’d written about Schaefer and Baltimore. He picked my brain dry. The Schaefer folks were thrilled. They practically gave Ben the key to the city. What they didn’t realize, however, was that Ben was yanking their chains.

When the story finally appeared in Esquire, it drew widespread attention for Cramer and earned him the full fury of Schaefer’s City Hall. They’d been spoofed, mocked and laughed at for their Tinker-Toy approach to municipal governance. One memorable line mimicked Schaefer’s “Litter Patrol” truck which, Cramer wrote, was used to “apprehend offending paper cups.” “Pink Positive,” the civic morale booster confection of Schaefer’s City Hall, got a Bronx cheer from Cramer as well.

Years later, through an intermediary, we had another albeit indirect encounter. A third party mentioned that Ben was writing a book about the baseball immortal, Joe DiMaggio, and was having difficulty tracking down a significant piece of information. I suggested that maybe I could help.

Ben had information that DiMaggio charged $50,000 for an appearance, and by circumstance of the calendar, DiMaggio had just appeared at the Orioles’ Camden Yards. I asked questions in the appropriate circles but sent word back through the third party that I was unable to verify the story even though there were conflicting claims of yes and no.

Robert Timberg, a colleague and competitor of Cramer from The Evening Sun, recalls Cramer in this manuscript in progress titled blueeyed boy, a post Vietnam memoir:

To me Richard had a goofy demeanor, but I must have had it wrong because he was irresistible to women judging by the way they flocked to him. He also personified a word just then coming into vogue—charisma. Everyone felt it, this larger than life quality. Once Richard and I were invited to a local political gathering on a boat docked on the Baltimore waterfront. I arrived on time, unlike Richard. “Where the hell’s Cramer?” someone asked. It wasn’t a friendly question. Richard had recently written a story raising questions a bout the ethics of one or two of the men on board. The others were pals of the guys he nailed.Richard was ten minutes late, fifteen minutes late… At last he came sauntering down the pier sporting this white, broad-brimmed Panama hat he usually wore, smiling broadly, clearly unapologetic about his tardiness. As he neared the boat, he picked up some grumbling that he knew came from the targets of his story and their cronies. As he stepped onto the boat, he swept the hat from his head with a flourish and flung it high in the air as if launching a Frisbee. I watched, as we all did, as the hat spun lazily over the water. Finally, it settled on the surface, bobbing happily, an image that said whoever had been wearing it now slept with the fishes.“Hey, look guys,” said Richard, pointing to the hat, “You got me.” With that he let loose a guffaw so boisterous and infectious that everyone, including men who moments before were thinking the darkest of thoughts about him, could not keep themselves from joining in.

I’d heard or read a story somewhere along the line, true or not, that Ben took so long to report and write What It Takes and spent so much time pursuing microscopic details that he exhausted all of his advance money and went deep into credit card debt before the book was completed. But that was the hallmark of Ben’s painstaking reporting skills right down to the last comma and dash.