I don’t often read Jacques Kelly’s column in The Baltimore Sun—or much else in the local paper, save the crime stories and Peter Schmuck’s coverage of the Orioles—mostly because his nostalgia beat about long-gone Baltimore isn’t all that different from the obituary notices. Last week, however, Kelly devoted his space to the 3100 block of St. Paul St., and as a onetime Hopkins student who frequented that strip almost every day, it evoked wasn’t-that-yesterday? memories. Kelly’s peg was a recent grease fire that’s temporarily (one suspects) closed the Charles Village Pub—“a revered local gathering place” struck me oddly, as when it replaced the dumpy (and racially infamous) Blue Jay Restaurant in the 1980s, it seemed like just another jock/sports bar—and he took off from there.

Kelly mentioned the forgotten Hopkins Store—the block’s corner outlet that my friend Alan Hirsch, for years, housed one of his Donna’s restaurants, after it closed—which was an under-appreciated place in my eyes. Kelly called it “a crammed variety store,” which is technically accurate, but really it had a bodega vibe, and it’s where I’d buy daily newspapers, cigarettes (40 cents a pack in 1973) and magazines. But the best part was shooting the shit with the young manager, Stu, a very cool hippie who didn’t have a mean bone in his body. Early on, we’d gab about sports and politics, and then, when I was editor of the Hopkins News-Letter, he was the first off-campus retailer who allowed me to drop off copies of the paper by the window. (Others that followed, egged on by non-campus stories, were Bread & Roses, the 31st Street Bookstore, Jen’s and Godfrey’s Steer & Beer.)

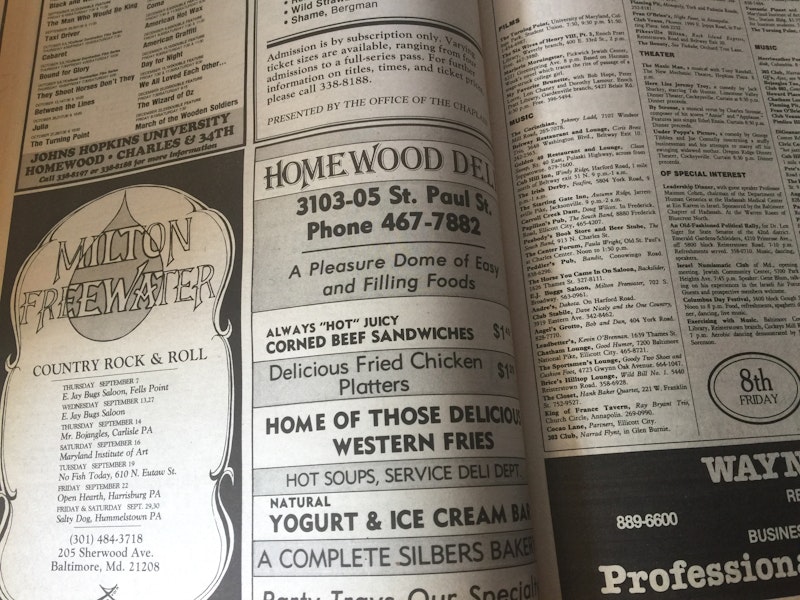

Even more significantly, a few words were spent on the Homewood Deli, an institution for some 20 years that, to my thinking, anchored the block. It was just a four-minute, tops, walk from the News-Letter office, and for a couple of years the garrulous manager Milton offered a loss-leader special: fat corned beef sandwiches for 99 cents. I must’ve eaten 100 or more of those during my time at the student paper and then, after Hirsch and I located our Baltimore City Paper on the 2600 block of N. Charles St., we’d often walk up there for lunch, usually with several colleagues/friends like Jennifer Bishop, Joachim Blunck and Harold Robertson.

We called the Deli “The Dome,” and it wasn’t until the other day that I learned the derivation of that nickname—I’d assumed we picked it up from the ads (pictured above) that ran in City Paper. Turns out, a Sun reviewer, in 1978, wrote, “The Homewood is an American dream come true, a pleasure dome of easy and filling foods for consumption on the premises or at home, a visual essay on what the Yank likes to eat and why he gets fat at 40.”

What a strange paragraph! Who the hell is “the Yank”? The Dome was a Jewish deli—though not on a par with Attman’s and Jack’s on E. Lombard St.—not a New England beanery. And while I suppose a steady diet of deli grub puts on the pounds if eaten in immoderate measures, that could be said for almost any restaurant, except, I guess, those that cater to vegans. I confined myself to the corned beef and excellent hot dogs—a few orders of fat, starchy “Western fries,” even covered in ketchup, cured me of buying any sides. I never had the lox and bagels, too pricey, but that was a draw for locals as well.

In any case, Milton was a good guy (at least by my non-employee reckoning) and he not only permitted us to give copies of City Paper there (over 400 copies a week picked up from our rack) but was an early and loyal advertiser as well.

I have a bound book that contains the first two years of City Paper (the first 10 issues called City Squeeze) and, inevitably, in taking a photo of a Homewood Deli advertisement, I got lost in reading some of the stories that are now 40 years old. For instance, our music critic J.D. Considine (who later wrote for The Sun, Rolling Stone and other larger, more lucrative venues), was way ahead of the crowd when writing about Blondie, Elvis Costello and the Sex Pistols. Considine, like many noted critics, was often temperamental, but in re-reading some of his reviews from that period, he was almost always on the mark.

One article, from the September 8th, 1978 issue, “The Missed Records of Jim Palmer,” by Eric Garland, was fascinating, an interview with the then-32-year-old future Hall of Fame pitcher who’s easily the best commentator today on MASN’s Orioles broadcasts. A short excerpt:

Garland: The clothing endorsements you do, the Jockey shorts, are they lucrative in the way Tom Seaver has pulled in a lot of accounts?

Palmer: No. Seaver was in New York and that’s where you have to be. I do the Jeffrey Bean as a favor; Jockey pays a standard fee. But Baltimore limits you. I had a friend who works in one of the largest agencies in town tell me I could get a lot more work. I said, “OK, you handle it.” He found out how limited you are in a city like this.

Garland: Did you feel awkward doing the underwear ads?

Palmer: No. Everybody wears it. At least most people do.

Finally, what struck me in looking at that issue is how many advertisers are no longer in business: Nyborg’s, Clark Street Garage, Grandma’s Candle Shop, Boutique Picasso, Bill’s University Sandwich Shoppe and Deli, John Gach Bookshop, Chick’s Legendary Records, Sundae Times, Green Earth Café, Long John’s Pub, No Fish Today, The Bead, Music Liberated, Gordon Miller Music, Penny Lane Record & Tapes, Beefmaster’s, Pecora’s Restaurant, The Clothes Horse, and Harvey’s Autosound. That’s just a small sample.

Granted, that’s the nature of the business; although in 1978 an independent retailer stood a better chance of survival than today. As did newspapers: as readers of this column, City Paper itself folded last year.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955