There are two sticks of dynamite hidden in a couple of recent documents that reveal growing disparities in Baltimore City. The first is that most of the city’s new wealth is concentrated around the Harbor while other sections of the city rot. And the second is that casino revenue is below expectations and failing to do its designated task of reducing property taxes.

The first swatch of paper, the Downtown Partnership’s annual “State of Downtown” report shows modest job growth, little new business, high office and retail vacancies but a major splash of new condos and apartments, especially near the water. The report reveals what urbanologists have been tracking—that young people want to live, work and socialize within a limited geographic area that is not reliant on cars. They juice kale and ride bikes. More to the point, they have the money to do it. There has been a significant growth in households with incomes of more than $75,000.

Here’s the distressing news. Downtown Baltimore is measured by a one-mile radius in any direction from Pratt and Light Sts., the locus of the city’s business district. What the report doesn’t say is that within those boundaries the city basically shuts down at six p.m. when the shades come down and the lights go on. And also within that designated plot, about 43 percent of the physical property is owned by non-profit organizations—colleges, churches, schools, hospitals—that pay no property taxes.

The city’s proposed budget, as reported, does not include a reduction in property taxes because revenues from the Horseshoe Casino have fallen well below projections. And the numbers might get worse when the MGM casino at National Harbor, the state’s sixth gambling emporium, opens next year. The alarm bell here is that it’s not wise to promise or spend money, as Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake has done, until it’s in the bank. She has prudently retreated on that commitment.

Rawlings-Blake had promised to reduce taxes on owner-occupied properties—more than double that of any other subdivision—by 20 cents by 2020, based on anticipated revenues from the casino. But the forewarnings have been that the more saturated the Maryland gaming market becomes the more the parts of the money-pie begin to diminish. People have a limited number of recreational dollars to spread around.

Nonetheless, Baltimore’s tax base grew by $1.3 billion last year, and that’s a healthy sign of interest and investment in the city. Neither the tax rate nor the petty-paced downtown economy appears to deter those who are drawn to the waterside colonies of condos and other downtown living spaces. After dark, Harbor East, Fells Point, Canton and Federal Hill come alive. Harborplace is so 1980s.

But the potential is enough to lure developers who are dramatically shifting the center of gravity in Baltimore with the friendly connivance of the ministers of influence at City Hall. And the millennials are willing to pay high rents—$1200-$1500 for a one-bedroom apartment—to be at the heart of the action. And the nexus for much of the activity is the Charm City Circulator, a public transportation amenity that unites the package even though it’s a money-losing convenience.

At Federal Hill, for example, the city is offering the venerable Cross Street Market for private development. It could become, with the right mix of shops, bars and eateries, the Belvedere Square of South Baltimore, a gathering place for the young people the city is trying to attract.

The problem is they’re not coming fast enough and when they do they don’t stay. And the reason is the lack of decent jobs and career opportunities. The I-95 corridor has a college presence and population that surpasses that of most states. Yet Maryland has never promoted the academic corridor as an education magnet.

So when four years are up, most students leave for opportunities elsewhere unless they remain in Baltimore to pursue careers in the medical profession, the city’s major employers. Boston, by contrast, has 63 colleges and universities in the greater Boston area and 25 percent of the students who graduate remain and work there, many along Route 128, Boston’s version of Silicon Valley.

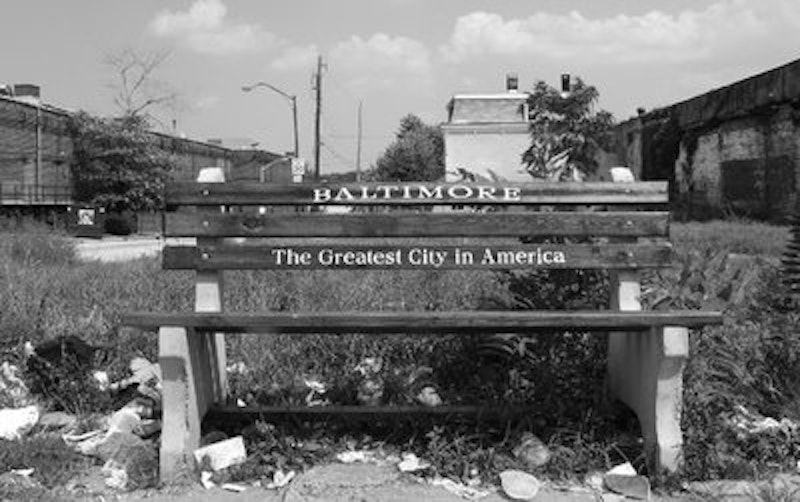

In addition to the newly gentrified neighborhoods around the harbor, a handful of other neighborhoods help to support the entire city—Roland Park, Guilford, Homeland and Mount Washington. Outside of those neighborhoods and the bracketed downtown area, the rest of the city is on life support and in decline.

A couple of decades ago, a program called “Move to Opportunity” was designed essentially to push people from the city to the surrounding counties to improve their lives. The plan was blocked. And what government failed to do with vouchers, Housing Commissioner Daniel Henson did with dynamite. He blew up public housing high-rises and forced those people who could to fan out into the counties, Section 8 vouchers in hand.

What’s left as Baltimore attempts to rebuild and repopulate is a home-grown version of the growing disparity in income and standards of living—a city where one-third of the people pay all of their taxes, one-third pay some of their taxes and the remaining third pay no taxes at all.

There are those who argue that high taxes drive people out of the city. That’s a bogus and disproved argument. There are enough programs to offset the tax rate which, in fact, is part of what drives the tax rate up for those who pay. What’s more, water rates and utility charges will soon eclipse the tax rate as a major cost of living expense. The cost of major repairs to the aging water supply system and the utility infrastructure are being passed on to consumers by government edict.

The city’s school system, though, is probably the most significant contributor to the flight of young families to the surrounding counties. To many, though, the suburban dream of a half-acre of grass enclosed by a white picket fence has lost its Norman Rockwell appeal.

There have always been economic and class distinctions, of course, but the widening gap underlines the cycle of many major cities—they rise, they fall, they die and are reborn. But part of the resuscitation and gentrification is producing yet another divide within the city of haves and have-nots in a way that defeats the purpose of inclusion and expands the growing extreme of two very distinct Baltimores. The same government that enforces inclusion is creating exclusion.

What’s happening in Baltimore and other major cities is really the sum total of what’s reflected in the overall economy nationally. There are fewer and fewer with more and more and more and more with less and less.

Trends do not begin in Baltimore. They come here to die. It’s a catchy irony that such a social and economic imbalance exists in this ethnic mosaic and liberal bulwark that used to pride itself for being quirky but risks becoming a dead end instead of a destination. A golden sliver is reserved for the Birkenstock crowd and the others are being left behind.