Now and again, with a shiver of little-boy innocence, I upbraid myself for exhibiting ridiculous naiveté. A few weeks ago we moved our Baltimore-based Splice Today offices from a congested Falls Rd. enclave to the relative quiet of Lower Charles Village. I’m still too young for full-circle end chapters, yet it’s an odd, but pleasing, coincidence that our new space in the 2600 block of N. Charles St. is right across the street from where, back in 1978, my first professional venture, Baltimore’s City Paper, was located.

I’d seen that Sunflower, a greasy spoon a few blocks south, had, unlike so many other places, survived the decades since I sold CP and left for Manhattan, and so I wandered down to get a cup of coffee. It was a disturbing, if not surprising, visit: of course the former jolly proprietors were gone, but instead of an active lunch crowd, with local office workers joking and making noise, the place was dark and shadowy, with the too-familiar plexiglass windows separating cashier from customer. I asked for an iced coffee, got a stare back as if I were from Damascus, and after some to and fro, we figured it out. A large coffee with a cup of ice and I was in business. Other spots are gone: Jimmy Wu’s, an okay 50s-style Chinese restaurant (in the same category as Waverly’s long-shuttered Golden Star); Love’s, a onetime institution in the area; and Josie’s, a small luncheonette run by a sweet husband-wife team.

The replacements for these establishments are anonymous all-you-can buffet dumps that I can’t imagine do much business. There’s a pretty fancy Safeway down the street—and I’m not too proud to admit my pleasure in discovering a Starbucks within—but like too many neighborhoods in Baltimore (save the Inner Harbor, Harbor East and Fells Point) Lower Charles Village has gone to seed. I’ve made this point before but it bears repeating: if the local government would aggressively offer tax breaks for development by individuals instead of for huge companies downtown—that don’t need them—this city would be measurably improved. There’s just no excuse for all the boarded-up storefronts and rowhouses on the main thoroughfares of N. Charles, N. Calvert and St. Paul Sts., let alone the extreme danger zones of East and West Baltimore. Sell a house to industrious residents for a buck, with incentives and conditions that have to be met and everyone’s better off.

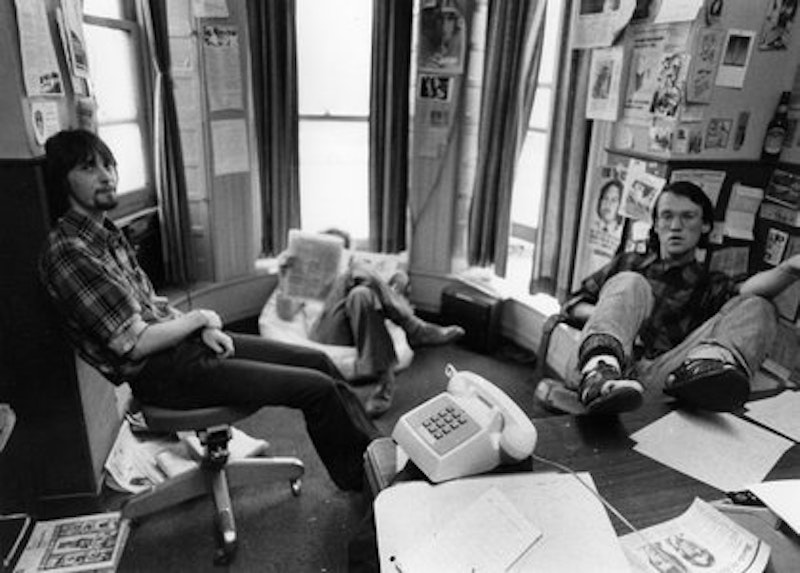

When CP took the first floor of 2612 N. Charles in ’78 (and eventually the entire building), it was a safer and more congenial neighborhood. I suppose that could be my memory playing cruel tricks, but not likely. Maryland National Bank was still around—closing at three p.m., which was crucial since ATMs hadn’t appeared yet—and most of the tellers were friendly and sympathetic when we couldn’t cash checks because of the paper’s lack of funds. It was an entirely different era, of course (Harborplace hadn’t yet been built, for example), and while the vestiges of hippie culture were drawing to a close, you couldn’t tell that by looking at our very young (and necessarily underpaid) staff. Another mystery peculiar to the times: we hooked up with an answering service for after-hour phone calls, but never received a bill. When my CP business partner Alan Hirsch asked one of the ladies why this was so, she just replied, “You don’t really want to know.” That was swell, and sure was a contrast to when I first rented space in Soho for New York Press in 1988 and was told by the landlord that we’d pay a fee every month for trash removal. When I said, “Not necessary, we can take bags to the dumpster ourselves,” Kenny looked at me, grimaced, and simply said, “No, that’s not how it works. Welcome to the city, sport.”

Our CP landlord, a splendid fellow named Alton—who appeared “old” to us, though he couldn’t have touched 55 yet—was extremely accommodating, never complaining about all the pot (and cigarette) smoke clouding the first floor, even though he must’ve thought twice when meeting clients for his insurance business. Alton got a little touchy at the almost constant explosion of very loud music—he wasn’t a fan of the Sex Pistols, Elvis Costello or The Clash that CP’s music critic J.D. Considine played—but that was rare. Alton appeared to be at a crossroads, preferring to play tennis or bridge to actually working, but the man had style and a big heart. He’d hired a slow neighborhood kid, Bill, as the building’s handyman and was protective of his charge.

Across the street there was a burger shack—a tiny, unattached building—where an enormous, bleached redhead imperiously ruled the roost. She was called Miss Ann, and, as we learned, it didn’t pay to get on her bad side. At first, after going there every morning for coffee and a muffin, or lunchtime sandwich, we were accepted as regulars, a happy relationship that continued for a year or two. Now, there were exalted regulars, like Alton, who’d get special off-the-menu items like fresh melon, a club to which none of us were ever invited, but we figured it was a matter of paying dues. Then, for some reason or another, Alan and I stopped frequenting Miss Ann’s for a couple of weeks—could be we switched venues, opting for Rudy’s a block away on 27th St.—and when we darkened her doors again we were met with the cold shoulder. As in, no service, bub. This didn’t sit well with either of us, an outright ban, but as the months slipped by and our colleagues Joachim Blunck and Jennifer Bishop returned to the offices with Miss Ann’s burgers, Alan and I reconsidered the feud. It could be that he got back in her good graces, I’m not sure, but this cowboy never did.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955