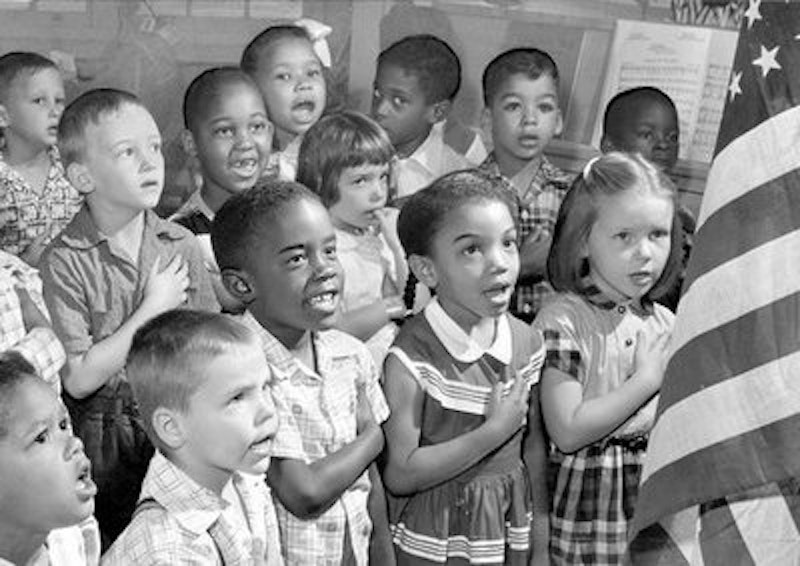

Coming to terms with my personal white contradictions and memories in 1964, I reflect on my introduction to integration at Garrett Heights Elementary School in Baltimore’s Hamilton neighborhood. Students were informed of the arrival of black children on school buses one morning. We were told we’d be assigned to, and welcome each student. White boys were to greet black boys and white girls greet black girls. It was very organized and exciting to be part of the welcoming committee. The big yellow school buses pulled into the playground and the black kids exited forming a single file line.

Before that morning, my only contact with anyone of color was a friend of my grandmothers’ who we called Aunt Josephine. She was a black woman who helped out doing laundry, and cooking. I won’t call her a maid because she never served us; she shared meals and attended family gatherings. But my grandmother gave her money and other things for her family. They worked in a textile “sweatshop” together sewing uniforms for the war machine.

Later that morning at school, I was assigned to a kid named “Domino.” We hit it off immediately and hung out on the playground after school before the busses returned to take the kids home. We talked about the Orioles and the Colts. All the kids got along well, and it was casual and natural. All the white parents in the neighborhood were upset. As children we couldn’t understand the reasons why, or the significance of the history unfolding before our eyes. Domino got his nickname after he was burned in a house fire that left his face scared with light and dark spots.

I never knew his real name because of an incident that occurred a few days later. I returned home that afternoon telling my mother how great Domino was. Then, I asked my mother what a “motherfucker” was. She screamed and demanded to know where I heard such a thing. “Domino,” I cried. She immediately dragged me, screaming “motherfucker,” up the hill right into the Garrett Heights School principal’s office. I was no longer allowed to hang out with Domino.

My parents, like the majority of whites at the time, were prejudiced. I still fight those ingrained feelings they believed and tried to teach by example. Saying my father was a bigot sounds harsh, but it was true. He’d say things like, “They’re not all bad but you can’t trust them” or “Don’t show them your money, hide it in your shoe, or they’ll take it from you.” “Cross to the other side of the street if you see them coming your way.”

It wasn’t cute or funny like the character Archie Bunker in the TV sitcom All in the Family. One of my father’s many rules was that if we kids brought black friends home after school to play, they had to stay on the porch and not in the house. I could also imagine black parents saying the same words to their children. Ignorance has no color.

When I was at Mergenthaler High School there were jocks, preppies, nerds, and freaks. I was a freak. A freak was not quite a hippie. We smoked pot and took LSD, but shunned Flower Power. We felt like outsiders when we were mocked and put down by other cliques and groups at school. We listened to rock ‘n’ roll and soul music and hung out with other black freaks like us. Jimi Hendrix was a major influence. Jimi’s music gave us a common bond, and was a reason why I picked up the guitar for the first time. Bands like The Funkadelics, The Last Poets, Sly and the Family Stone, and James Brown were an entire universe unto itself. WEBB radio station in Baltimore was owned by James Brown. Soul music and rock ‘n’ roll, the Woodstock Festival, the Vietnam war protests, the Civil Rights movement, plus our contempt for Nixon and a basic fear of the police united black and white youth like no other time in recent history. Revolution was brewing. Protests were happening around us. You could feel the culture shift.

For one bright moment in our collective consciousness, it appeared that the very thing that divided us was bringing us together. Radical groups like the SDS, The Weathermen, The Black Panthers and the Yippies were delivering us from evil. But America’s entrenched powers neutralized the youth movement— and the progress achieved from the Civil Rights and anti-war protests—rendering it useless and creating the tense racial vacuum that still exists today. The assassinations of Malcolm X, Dr. Martin Luther King, and the Kennedy brothers permanently closed any hope of meaningful change.

Movements like the Beat Generation were born out of a restless age where blacks and whites came together and shared as one people, one mind, combining jazz, hipster culture, and poetry to invent a new art form. Out of that came the unrest and revolt of the 60s, evolving into the punk rock movement and rap music culture of the 70s and beyond, evolving yet again. There is something in the air. We have more in common as Americans than we realize. We grow numb and weary from the daily dose of lies we’re fed by politicians and their media puppets.

During my college years as part of a Sound & Visual poetry class, I conducted an experiment one sunny summer day. I purchased some make-up from a theatrical shop, and an Afro wig. At home I applied the golden brown face paint and donned the “bush” style wig. I had a natural look, not like the exaggerated blackface “minstrel.” I walked from my apartment on 21st St., four blocks to the Rite Aid drugstore. On my way there no one noticed me. It was a beautiful day and the streets were filled with people. Yet no one noticed me. I stood in line with blacks and whites, and waited my turn. Not a second glance. Then I ordered a pack of Kool cigarettes from the cashier, who was black. She said nothing and acted like nothing was amiss. Even though my hands were still white. No one said a single word. They surely saw me, yet they didn’t see me. They didn’t even look at me funny. I felt like the invisible man.

I guessed that’s how blacks felt. Like no one saw them. Not even each other. That day changed my perceptions. It reinforced my commitment not to be like my parents’ generation.